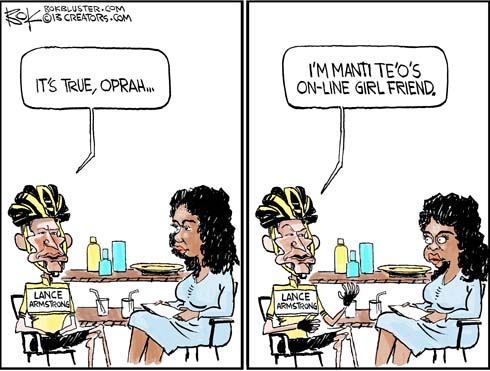

The world’s most famous cyclist, Lance Armstrong, lied and lied and lied, and even sued a news organization who called out his lies. (He may have even lied while backpedaling for Oprah.)

Notre Dame defensive player Manti Te’o, whether he meant to or not, lied about what turned to be an imaginary girlfriend.

The result is another round of hand-wringing about the “diminished role” of investigative journalism and media who, as National Public Radio wrote, “let its guard down.”

It should be “let their guard down,” because media are plural, dangit. But confusing media as a singular entity helps prove the point of this post, which reminds us that even as lots of journalists failed to catch the lies, eventually a journalist caught the lies.

It’s tough to be a journalist, because lots of people and organizations lie to you (and, by definition, to the public), stonewall with “no comment” or piecemeal answers, provide general “statements” on a topic instead of answering specific questions, or bend their answers so far in their own favor that the truth is broken by most ethical standards.

More than once I heard Randy Henderson, my late city editor at The Birmingham News, say to a caller complaining about a story: “We print lies every day, because people lie to us every day.” Journalists cannot look into the hearts of others. Journalists don’t have subpoena power but must be more exacting than prosecutors, because a prosecutor who loses a criminal case won’t face libel charges.

In the case of Te’o, I’m reminded of this scene from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, in which principal Ed Rooney is right when he doesn’t believe that Sloan Peterson’s grandmother is dead. He calls out Mr. Peterson (that is to say, Ferris) on the phone:

Oh, sure. I’d be happy to release Sloane. You produce a corpse and I’ll release Sloane. I want to see this dead grandmother firsthand. … That’s right. Just roll her old bones all over here and I’ll dig up your daughter. It’s school policy.

A journalist wouldn’t do it that way, of course, and even Principal Rooney was snookered by Bueller, a high-quality liar.

I believe it’s tougher than ever for journalists to move beyond the carefully constructed PR façade of athletics, much less catch liars, in this age when top college athletic departments censor their own athletes, restrict journalists’ access, seek to dictate what can be reported, pressure journalists who oppose the PR line, and bypass media gatekeeping with information delivered to a public that may not distinguish the difference or want to kill the messengers who deliver bad news about their favorite teams. (Feel free to replace the references to athletics with “politicians,” “radio morning-show hosts,” “businesses,” or other liars as you wish.)

This does not excuse bad journalism, of course, and there’s plenty of that to go around. Many journalists don’t ask the right questions, don’t want the truth to impede on a good story, are too busy feeding the never-sated digital beast, or want to believe that people are basically good, or lots of other reasons.

The (sort-of) good news: In the cases of Lance and Te’o and others, remember that journalism eventually did its job:

- Even as Armstrong lied and lied and sued and lied and intimidated and lied, some journalists continued to pursue the truth.

- It wasn’t until after the Deadspin story that Notre Dame, which knew about the hoax possibility for weeks, hastily called its press conference and (began to) explain the situation. Meanwhile, Te’o admits that he “tailored” accounts of his story, even after Notre Dame says it had begun its investigation.

- We can go on, with examples of Olympian-turned-felon Marion Jones and plenty of presidents (Nixon, Clinton, etc.), presidential candidates and many more famous people who invested years lying to journalists.

The world’s ability to lie outstrips journalism’s ability to call out the liars. And in this world of more-and-better liars and fewer journalists, it’s not getting easier.